It’s not uncommon to see the rhetorical question “What Would Jesus Do?” (WWJD) bandied about in the ether of the intertubes.

Sometimes the question is asked as a means of laying down a virtue marker in the questioner’s favor, but often it’s an honest challenge. The question is usually rhetorical, however, because the person asking knows that (1) Even if answered, few people will act on it; and (2) Everyone knows the answer, but it’s usually the opposite of what most people intend to do. Hence, the virtue signaling.

But in fairness to us ordinary human beings, “What Would Jesus Do?” is a trap of sorts, because whatever we think Jesus would do is comparatively easy for Jesus to do, given that he was not only human but divine. The rest of us have oversized clay feet and tying our ethical shoelaces is a challenge. We certainly need a scanning electron microscope to find the spark of the divine that we’ve been assured is within us.

But what about someone who insists, “I am an ordinary human being”? What of his or her ethical pronouncements? We could dismissively relativize them as “one person’s opinion,” but that means our ethical standards are also easily dismissed, so that’s a zero sum game.

“I am just a human being,” The Dalai Lama says. [1] What if we asked, “What Would The Dalai Lama Do?” (WWDLD)? Of course, this could devolve into virtue signaling, but we no longer have the luxury of the “But he’s divine” dodge. Yes, the world (or much of it, anyway) considers the Dalai Lama to be a holy man, so a partial dodge, a feint to the right, is an option, if we’re so inclined, because few of us are holy. Like determined toddlers, we’ll always find a way out of behavioral expectations, which we determinedly and with some alacrity toss aside like an itchy wool sweater.

But, at The Dalai Lama’s insistence, the emphasis is on “man,” not “holy,” so the dodge is, at best, iffy. The Dalai Lama insists on his humanness, which he ranks as his most important attribute, followed by “I am a Tibetan” and “I am a Buddhist monk.” Only after establishing his “ordinariness” does he state, “I am The Dalai Lama.” [2]

Why give him the time of day? Why him, and not our next door neighbor, who has years of experience growing great tomatoes? Well, for tomatoes seek out the neighbor with the experience (although The Dalai Lama is a gardener), but for other questions, different criteria apply. We listen to The Dalai Lama partly because of the opinions that we receive from other people we respect, and partly based on our estimation that he’s engaged thoughtfully and rigorously, over a long period of time, with important questions.

So, given the multiple crises we face – the COVID-19 pandemic, collapsing economies and rising inequality, racism and xenophobia, the rise of authoritarian cults, and the climate catastrophe – What would The Dalai Lama Do?

He’s given us an extended answer.

“Compassion,” he says, “what I sometimes also call human affection, is the determining factor of our life. Connected to the palm of the hand, the five fingers become functional; cut off from it, they are useless. Similarly, every human action becomes dangerous when it is deprived of human feeling. When they are performed with feeling and respect for human values, all activities become constructive.”[3]

In his essay, Human Rights, Democracy, and Freedom, which he wrote in honor of the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, he elaborates in some detail what must be done: [4]

“Whether we are concerned with suffering born of poverty, with denial of freedom, with armed conflict, or with a reckless attitude to the natural environment everywhere, we should not view these events in isolation. Eventually their repercussions are felt by all of us. We, therefore, need effective international action to address these global issues from the perspective of the oneness of humanity, and from a profound understanding of the deeply interconnected nature of today’s world.”

“At birth, human beings are naturally endowed with the qualities we need for our survival, such as caring, nurturing, and loving-kindness. Despite the fact that we already possess such positive qualities, however, we tend to neglect them. As a result, humanity faces unnecessary problems. We need to make more efforts to sustain and develop these basic qualities. That is why the promotion of human values is of primary importance.”

“We also need to focus on cultivating good human relations since, whatever our differences of nationality, religious faith, race, wealth, or education, we are all human beings. Faced with difficulties, we always meet someone, a stranger perhaps, who spontaneously offers us help. We all depend on each other in difficult circumstances, and we do so unconditionally. We don’t ask who people are before we help them. We help them because they are human beings like us.“

“Our world is increasingly interdependent, but I wonder if we truly understand that our interdependent human community has to be compassionate; compassionate in our choice of goals, compassionate in our means of cooperation and our pursuit of these goals.”

[…]

“Concerned not only for ourselves, our families, our community and country, we must also feel a responsibility for the individuals, communities and peoples who make up the human family as a whole. We require not only compassion for those who suffer, but also a commitment to ensuring social justice.“

[…]

However, responsibility for working for peace lies not only with our leaders, but also with each of us individually. Peace starts within each one of us. When we have inner peace, we can be at peace with those around us. When our community is in a state of peace, it can share that peace with neighbouring communities and so on. When we feel love and kindness toward others, it not only makes others feel loved and cared for, but it helps us also to develop inner happiness and peace. We can work consciously to develop feelings of love and kindness.”

[…]

Peace and freedom cannot be ensured as long as fundamental human rights are violated. Similarly, there cannot be peace and stability as long as there is oppression and suppression. It is unfair to seek one’s own interests at the cost of other people’s rights. Truth cannot shine if we fail to accept truth or consider it illegal to tell the truth.”

So, the answer to “WWDLD?” is distressingly similar to “WWJD?”: “Love one another as I have loved you.”

Unfortunately, that’s precisely the thing we don’t want to do.

[1] Tenzin Gyatso, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama; Stril-Rever, Sofia (ed.); Mandell, Charlotte (tr.). 2010. My Spiritual Journey. HarperOne Reprint, Kindle version., p. 17.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, p. 20.

[4] Tenzin Gyatso, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. 2008. Human Rights, Democracy, and Freedom. Statement for the sixtieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, December 10. All quotations that follow are from this essay, and emphasis has been added throughout. The full essay is available online at: https://www.dalailama.com/messages/world-peace/human-rights-democracy-and-freedom

I’ve been decompressing the last few days. A bit of a chest cold, which makes me wary with worry, wondering will I wrangle with Streptococcus pneumoniae? Or just Beowulf-style alliteration? Certainly, there are Grendels about.

I’ve been decompressing the last few days. A bit of a chest cold, which makes me wary with worry, wondering will I wrangle with Streptococcus pneumoniae? Or just Beowulf-style alliteration? Certainly, there are Grendels about. Grendel, the monster, was more merciful: he dispatched Hrothgar’s men quickly.

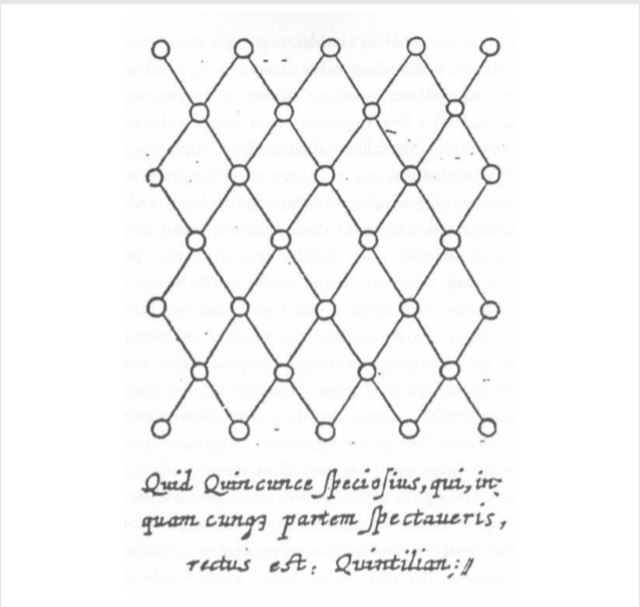

Grendel, the monster, was more merciful: he dispatched Hrothgar’s men quickly. And there is detail. And more detail. There are long skeins of connections between details. There are long skeins of connections between the long skeins of connections. Many deaths in the first few chapters, most natural but nonetheless melancholic and perplexing. Memory and the loss of memory. French literature and sand in Monsieur Flaubert’s brain (the French think of everything). A 17th century physician’s missing skull. An approach to knowledge that is described by a complex geometric shape, which I find appealing. Personal and civilizational decay. A mansion conspicuously constructed to consume the wealth of an upstart Englishman, now subsiding into genteel decrepitude. World War II and carpet bombing and firestorms. The Garden of Cyrus. Or, The Quincunciall, Lozenge, or Net-work Plantations of the Ancients, Artificially Naturally, Mystically Considered (1658). Silkworms and Nazi death camps.

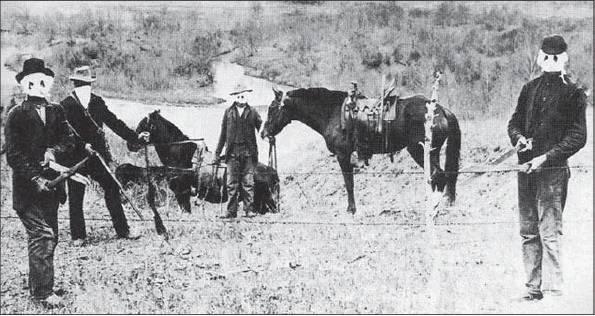

And there is detail. And more detail. There are long skeins of connections between details. There are long skeins of connections between the long skeins of connections. Many deaths in the first few chapters, most natural but nonetheless melancholic and perplexing. Memory and the loss of memory. French literature and sand in Monsieur Flaubert’s brain (the French think of everything). A 17th century physician’s missing skull. An approach to knowledge that is described by a complex geometric shape, which I find appealing. Personal and civilizational decay. A mansion conspicuously constructed to consume the wealth of an upstart Englishman, now subsiding into genteel decrepitude. World War II and carpet bombing and firestorms. The Garden of Cyrus. Or, The Quincunciall, Lozenge, or Net-work Plantations of the Ancients, Artificially Naturally, Mystically Considered (1658). Silkworms and Nazi death camps. Between 1889 and 1893, there were a series of violent clashes between large cattle companies and smaller settlers in Johnson County, Wyoming. The fight is known as the Johnson County Wars or the Wyoming Range Wars. The cattlemen and the settlers were battling over grazing lands and water rights, with the cattlemen insisting they had the absolute right to all grazing land and water. The settlers disagreed. The cattlemen brought in hired gunmen, and the settlers joined together to form a posse of 200 men to resist. Eventually, the U.S. cavalry and the Wyoming state legislature gained some measure of control, but the fighting persisted for years.

Between 1889 and 1893, there were a series of violent clashes between large cattle companies and smaller settlers in Johnson County, Wyoming. The fight is known as the Johnson County Wars or the Wyoming Range Wars. The cattlemen and the settlers were battling over grazing lands and water rights, with the cattlemen insisting they had the absolute right to all grazing land and water. The settlers disagreed. The cattlemen brought in hired gunmen, and the settlers joined together to form a posse of 200 men to resist. Eventually, the U.S. cavalry and the Wyoming state legislature gained some measure of control, but the fighting persisted for years. I’ve missed a few days of entries. We were preparing to move from Madison to Appleton, and while I couldn’t physically participate in the preparation, I was distracted.

I’ve missed a few days of entries. We were preparing to move from Madison to Appleton, and while I couldn’t physically participate in the preparation, I was distracted.

I wrote this in response to a question posed in a Facebook group. The question was, “Is the anti-science sentiment of the Trump administration new to America?” The answer, alas, is no.

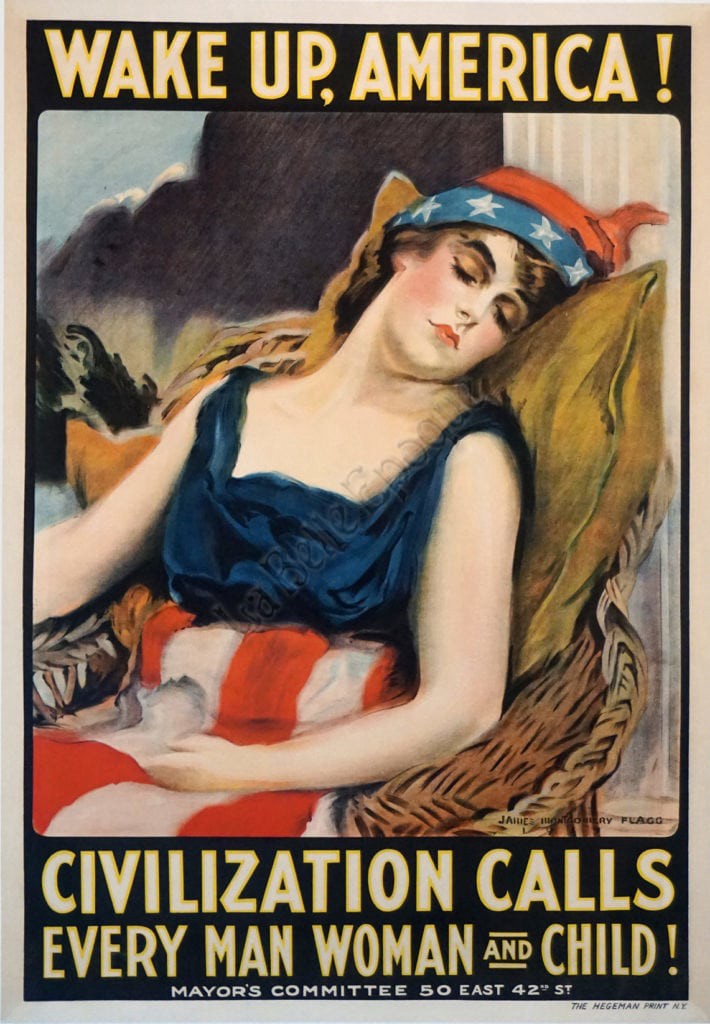

I wrote this in response to a question posed in a Facebook group. The question was, “Is the anti-science sentiment of the Trump administration new to America?” The answer, alas, is no. Modern advertising arose from the propaganda techniques developed by Edward Bernays and others when, at the request of Woodrow Wilson, they “sold” America’s entry into World War I to an initially reluctant public (plus Wilson jailed anti-war protesters, most notably Eugene Debs).

Modern advertising arose from the propaganda techniques developed by Edward Bernays and others when, at the request of Woodrow Wilson, they “sold” America’s entry into World War I to an initially reluctant public (plus Wilson jailed anti-war protesters, most notably Eugene Debs).